The second the Berlin Wall came down and the US ostensibly won the Cold War, Hollywood seemed to have skipped over the introspection and dived back into the simple black-and-white moral absolutism of WWII with the likes of Saving Private Ryan and Schindler’s List. We had our Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now but those were meditations on the pointless sadism of war, merely using the Cold War as a backdrop. We have seen films that evoked the paranoia of the era (The Invasion of The Body Snatchers), films that use it as background dressing for thrillers (The Hunt For Red October and The Manchurian Candidate), spoofs like TV’s Get Smart and the jingoistic indulgence of the Rambo series. However, there has never been an exploration of the Cold War as an actual experience that a significant portion of American citizens having lived through.

A part of that might be because the Cold War coincided with a growing awareness of ambiguity within our ranks. Vietnam exposed the horrific ambiguity and sadism of war, Nixon dispelled the myth of the presidency and McCarthyism sowed discord and started witch-hunts between brothers and neighbors. There was just no room for the simple narratives of John Wayne-esque good versus evil. The Cold War was a war that no one wins, that even the victors carry scars that are still visible today. The instability in the Middle East, the uncomfortable specter of Christian fundamentalism and conspicuous consumer capitalism as tenets of American identity; all of these and more the standing legacy of American reactions to the Red Scare.

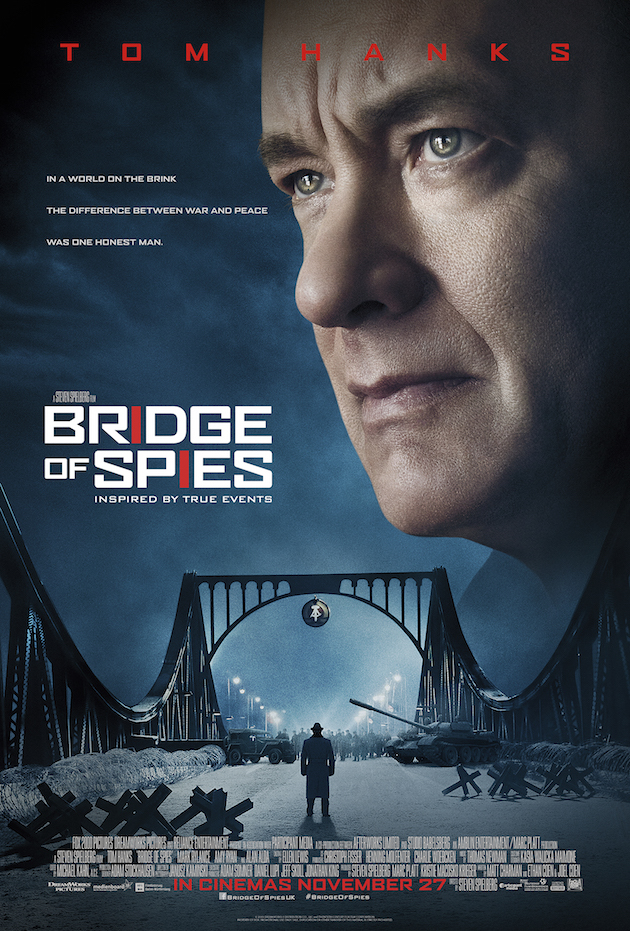

Bridge of Spies is Steven Spielberg’s triumphant return to the director’s chair for the first time since Lincoln in 2012 and it might just be the most humane film to have ever been made about the Cold War. Spielberg’s America is lived-in and authentic with families discussing Julius and Ethel Rosenberg at the dinner table and children staring bleary-eyed at cartoons teaching them how to duck and cover or fill their bathtubs with drinking water in the event of the eventual attack by the Soviets. This is a film about the paranoia, fear and hatred that permeated American society but Spielberg also has the audacity to propose that the best weapon that Americans could have against a red menace was upholding the virtues that the United States was founded on.

To wit, Bride of Spies follows James Donovan (Tom Hanks), a New York insurance lawyer who was volunteered to defend Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance), a painter accused by the US government of espionage. It is a thankless task, as Donovan describes it “everyone’s going to hate me but at least I’m going to lose”. The whole thing is an elaborate show that the United States was a nation of laws that even her enemies deserved the protection of a fair trial. What they never counted on was that Donovan is a man of principles with an unshakeable faith in the American Constitution. He refuses to let the American legal system turn into a kangaroo court and seeks to represent Abel to the best of his abilities to the chagrin of his colleagues and at great risk to personal safety and the safety of his family. Eventually, Abel is spared the electric chair on the grounds that he is more valuable as a bargaining chip alive should the Soviets ever capture an American operative. That American operative turns out to be Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell), a gung ho, square-jawed, All-American Air Force pilot. Once again, Donovan is pulled in and sent to East Berlin to negotiate the exchange.

Tom Hanks reasserts his credentials as one of the greatest leading men of this or any generation of actors. Jim Donovan is one of those roles that were designed for the likes of Henry Fonda but in the hands of cinema’s quintessential everyman Hanks’ Donovan is less of a unyielding moral pillar but instead channels an exasperated determination. He feels like the only sane man in a world of subterfuge that refuses to acknowledge anything concrete and communicates primarily in doublespeak. In this case, he understands that the United States was built on a foundation of principles and to succumb to the fear and hysteria to execute and mistreat the “monster” is to prove that the Soviets were right. It is with this idealism that he braves public outcry and potential professional ruin. He is the prototypical Spielbergian protagonist; men like Oscar Schindler and Abraham Lincoln; ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances, refusing to compromise their principles and simply skate by doing the bare minimum and thus end up overreaching for greatness. Hanks always had an innate ability to find the nobility within the average man and it is breathtaking to watch here.

Hanks’ performance is rivaled by Rylance as the convicted Soviet spy, Abel. Rylance finds the heart of Rudolph Abel as a stoic patriot. He is neither villain, nor traitor. He is simply a soldier serving his nation with pride and nobility, no different from the same men and women who are doing exactly that in the name of American interests. Instead of being a caricature, Abel is a soft spoken man with simple tastes and an intense humanity. There is a level of quiet dignity as he faces the prospect of remaining captive within American custody as well as an uncertain future should his Soviet spymasters believe that he has already compromised them. More importantly, his presence raises the question of what it makes America look like should we succumb to our prehistoric need to quarter and lynch him publicly. Spielberg creates an interesting parallel between Abel and Powers. While Abel is stoic and resigned, Powers is the embodiment of jingoistic bravado until it is exposed as a veneer upon his capture. He is just a scared young man caught behind enemy lines, just as Abel should be but is not. Along with Hanks’ performance, it creates a running theme of ordinary men trying to survive in circumstances bigger than they can ever imagine.

Bridge of Spies might not be the flashiest film that Stephen Spielberg has ever made but he brings a trademark precision that many directors can only dream of. The best things about his direction are the things that he refuses to do. Instead of proselytizing about the virtues of the west, he understands that the only assurance we need that our system works is a glimpse of three East Berliners getting gunned down as they try to scale the Berlin Wall. Instead of creating caricatures of the Soviets, he paints them as resigned bureaucrats “having the conversation that their countries cannot”. He fights the temptation to turn Bridge of Spies into a more traditional spy flick or action series; the espionage more about the subterfuge, negotiation and deal making; more Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy than 007. His version of James Donovan is not Jason Bourne, but just a tired man with a cold who wants to go home.

All this coupled with beautiful cinematography and an understated musical score that only kicks in deep in the movie when he is being tracked by an agent, a sign that the danger is starting to become real. His East Berlin is bathed in a melancholic blue, contrasting beautifully with the Rockwellian glow of Brooklyn and the more subdued optimism of West Berlin.

The opening of the film begins with Abel painting a self-portrait with Spielberg framing the shot so that it contains Abel’s reflection in the mirror, his painted self-portrait and himself in the middle. This is Spielberg’s manifesto for the film as an exploration of reflections. There is the instantaneous reflection of self in the mirror of society and the enduring portrait that has been contextualized by time and history. When Abel gifts Donovan with a portrait that he painted of Donovan while in prison, the symbolism becomes clear. That the lasting legacy we leave as a nation is our duty to do what is right, no matter how difficult and unpopular that may be. That the greatest weapon that we had in our arsenal against the enemy is not nuclear or mechanical but within our willingness to find and remember our common humanity.

Considering the quagmire that the United States (and by extension the world) has found itself in since the 1950s, it’s nice to be reminded of that once in a while.